- Home

- Jodie Patterson

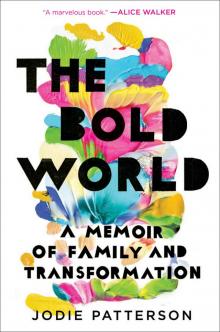

The Bold World Page 9

The Bold World Read online

Page 9

“You’re so juicy,” he says, squeezing my thighs. “It’s like your friend said the other night: Pregnant Jodie is the tricked-out version of Jodie!” We laugh, his hands gliding up my leg, resting on my butt. I stay put so he can look at me, my growing belly, my big smile—and let him take it all in.

Serge and I have finally made our way back together.

Post–South Bronx, post road trip across America with Grandma Gloria, I got a new verve. Over the three weeks we spent together, joyfully living out of her car, we experienced so many firsts, in places I’d never much thought about as a city girl, like New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado. We’d driven into their sunsets, climbed their mountains, strolled through canyons, deserts, and ruins alike. And in just about every state we visited, we slept roadside once or twice, when our yellow Cadi just couldn’t go another inch. We’d wrap ourselves in blankets and watch the stars from our car window until daylight emerged and we could safely walk to the nearest gas station for help. With so many stunning moments under my belt, I returned to New York and jumped back into my life with a vengeance. It was time, I thought, to get to work.

Soon after my trip I made sure to run into Serge. One night I went to his restaurant, hoping he’d be there but not knowing what to expect. We hadn’t spoken to each other in months, but after our eyes met across the crowded dining room, we sat and talked for hours, shoulder to shoulder, catching up. I told him about Jacinda and the college boys who had cheered me on, and all about my adventures in Grandma Gloria’s yellow Cadillac. I told him everything I had gained—the confidence, the strength—along with what I felt I still didn’t have but wanted. Him, mostly. Serge listened without judgment, focusing on the stories and the bravado and the lessons learned—all the while holding my hand, letting me unfold.

“I really miss you, Serge.”

“Me, too, Jo…I miss you a lot.”

I went home with Serge that night, and we spooned in bed as though we hadn’t missed one evening together. His soft skin felt the same, his sheets smelled just as they had months ago. Half-read newspapers were still thrown about his bedroom floor, and the paintings of naked women he so loved were still propped up beautifully against one wall, creating a collage of images in his room, Serge’s feminine shrine.

It was as though time had stood still for us, as if the other men and the other women, and all the experiences that had manifested in between our “goodbye” and “hello again,” were food for thought, forcing us to think about life and ourselves in new, better, more insightful ways. The next morning, Serge asked me to move back in, and I agreed.

Life moved forward. Just before my twenty-seventh birthday, we got married at the courthouse in lower Manhattan on a Thursday with my best friend, Amani, as the sole witness. I wore black leather pants, Serge wore jeans. We bought rings in Chinatown on our way to the courthouse, and when we said our vows, we felt every moment of happiness in the kiss that sealed a new “us.”

Soon after we married, I landed a job working for a friend of mine who had started his own music label, Cheeba Sound, and needed an assistant. It felt like an opportunity of a lifetime—to work on something from the inside out, to finally, finally create.

I was quickly thrown into the center of the action. I did everything from answering phone calls to writing press releases for our one and only artist, D’Angelo. Even the mundane elements of my job thrilled me. We were helping someone we believed to be one of the most righteous artists out there do what he did best: make beautiful, iconic music. We knew D’Angelo was special, that he represented something we didn’t see often enough in the public landscape: a Black man who—as my friend once said—“debunked the stereotype that Black men dwelled in only two emotions, lust and anger.” Sonically, lyrically, aesthetically, D’Angelo combined both masculine and feminine, pretty and ugly, tough and tender. It was our obligation to share D with the world—and I was excited, finally, to set out to work each day to meet the challenges of that task.

Our weddings couldn’t have been any more different. Serge and me, low-key at the courthouse.

Mama and Daddy dressed to the nines at church, in Virginia.

Just months before D’s album was completed, I found out I was pregnant. Serge and I hadn’t planned it—and I was terrified. “I can’t have a baby, Serge—we live in a walk-up!” I protested, sitting on our bed, cross-legged and sobbing. “And I have a job!” Another good reason, I thought, not to upend our lives. The list went on. But in our tiny room on Sixth Avenue, Serge struck down all my points with reason: Jobs are a good thing when people have children—and if you don’t want to work, that’s fine, too; A move might be smart anyway; We can do this. Serge held my hand in his hands. This is a great thing. He nudged at my fears with promise, picking them apart with hope.

“This baby’s going to be special,” I told my dad over the phone, breaking the coldness that had existed between us for far too long. We hadn’t been in the same room without noticeable tension since he’d squashed my graduate school plans a few years before. Most of our interactions were buffered—we communicated through notes delivered by mail and over sit-down dinners in busy restaurants with plenty of ambiance to distract us. When Serge and I eloped, I sent Daddy and the rest of the family a very simple note relaying the news. Whenever a new life event happened to me, I’d shoot him an update and he’d tell me he was proud, or happy, or surprised: “You’re something special, Jodatha.” There was love between us, always, but there was also strain.

But this baby, I thought, meant something bigger than either of us. And I wanted him to be part of this life I was creating.

Late into my first trimester, the golden-haired child entered my dreams. Over and over in my sleep, visions of the baby would come to me—a boy with hair the color of gold, enveloped in a warm light beam. In those vivid dreams my baby felt strong and determined and independent, as though he was going to take on anything. We would name him Malcolm or Isaac or Toussaint—something befitting the gifts he would no doubt bestow upon us all.

I’ve wanted to be a mom from as far back as I can remember. When people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would say: a mom, a teacher, and a businesswoman in a suit. I loved the way my mother mothered us, and I often daydreamed about what I would be like with my kids when I had them someday.

I always envisioned myself having daughters. My family was surrounded by female trilogies—me, Ramona, and my mom. My grandmother Gloria and her daughters. My older sisters from my father’s first marriage and their mother. Girls were what I knew.

Matriarchy defines our family—all the women, from my great-grandmother all the way down, were leaders. Church congregations listened to them speak on Sundays, students were inspired by them in the schools where they taught, husbands and children leaned on them at home. We were Blackwells, Rackleys, Pattersons. When I look back at what our family had amassed in life, much of it was built by the hands of women.

And yet, when I felt my baby’s strong spirit in those visions, when I thought “unique,” “blessed,” “purposeful,” the image that manifested was “boy.” A woman’s strength, I thought, is seldom gifted to them, it must always be nurtured. But a man’s is written into his DNA before he’s even born.

In retrospect, when I was conjuring this boy child, I think I was actually dreaming of someone uninhibited and free. And that was certainly who Georgia, my baby girl with blond, bushy ringlets—the golden-haired child of my dreams—would eventually show herself to be.

SECOND TRIMESTER: CREATING

“Go around me, people. Move along!” I murmur under my breath as I move through town, making my way to work each morning in no particular hurry. I’m not changing my pace for anyone. Joined with this baby, I walk with a slow, steady purpose. Girth has freed me from my anxiety—the old fear that I’ll float away or be overpowered. It’s a

s if those worries never existed.

I enjoy witnessing my body morph into something else, something I’ve decided is more beautiful. I take long showers and watch the soap drip over this new shape—my thickening thighs and legs, this ever-expanding middle—and I feel euphoric. Sometimes I break into a stupid grin when I get undressed. Finally, I am the Chubby Black Girl I’ve always wanted to be! At almost two hundred pounds, I am the weight and substance I’ve always envied. I carry them for the first time, not just as a feeling, but physically, on my body. I’ve never felt so aligned.

By the fourth month, I’ve gotten to know the baby’s rhythm—when she sleeps, when she wakes. I eat two gummy bears and feel her start to wiggle, a sugar rush dance she likes to do. She and I, we have lots of conversations: what she might do with her life, who I will be for her. This being growing inside me, gaining strength with my own blood and bones, is the best thing in the entire world. I hold on to the feeling like a delicious secret. I feel lucky—lucky to be pregnant, to be growing. Lucky to be creating. Together, we start plotting our future.

At work, as in my body, I feel integral. I leave the office each night feeling that I’ve put my hands on every big idea, every decision and challenge that lands on our desks. Our team is a close-knit, motley crew, full of the frenetic, excited energy that often comes when you’re young and every experience feels brand-new. We do things our way, not bothering to follow the rules of the industry, not thinking one minute about protocol or repercussions. Protecting D’Angelo and his creativity becomes a kind of mission. A preview for me of what it means to safeguard something that others don’t quite understand.

At home, Serge and I are a force. His somewhat vague idea of a “venue that transforms” has finally come to fruition. He names it Joe’s Pub, an intimate, beautiful live performance venue housed inside lower Manhattan’s legendary Public Theater, established by Joseph Papp, where musicians, actors, comedians, and spoken word artists of all stripes will have a home. Joe’s Pub is our enterprise—our second baby in addition to the one getting heavier by the week inside my belly. With Serge at work building the space, I set about the task of filling it up. Musicians like Questlove, from the Roots, and Bilal, whom I’d met through D’Angelo, become among the first artists I book for Joe’s inaugural set of shows.

For the first time Serge and I work together professionally, and it makes me feel womanly, responsible, and capable. And when Joe’s Pub finally launches, the response is overwhelming. Hundreds of people line up, swarming to get in. It feels as if my life is on fire and my nerves are exploding each day.

THIRD TRIMESTER: LIFE

On July 31, 1999, after thirteen hours of intense back labor, our spines scraping against each other on her way out, she finally comes. And simultaneously, I commit my first godlike act: birthing. Childbirth is beyond what all the yoga classes prepared me for, eclipsing the coaching and the massaging, immune to the Reiki my mother attempted to perform on me in the birthing room, and the Sade I insisted on playing in the background. The birth plan that Serge and I had so meticulously crafted, detailing the perfect conditions for our baby to enter the world, was cast aside after hour eight.

There’s no borrowing of perseverance or will or motivation to get you through the act of birthing, I realize. There’s no easy way around it, no ducking the pain or the fear. You feel it all, because you have to. And in the process, you understand what it really means to move between giving it your all and giving in to nature. That ability—to go from one extreme to another—feels almost supernatural. After creating Georgia, I’m convinced that I am invincible.

Toward the end of the pregnancy, I made the decision to press Pause on the record label job and Joe’s Pub until after Georgia was born. My feet had ballooned to almost double their size and I couldn’t keep up with the physical pace my work required. But now, confronted with the prospect of picking up where I left off, I’m not sure I want to.

In the many, many quiet hours spent alone with my new daughter, I begin to think—about what we might do with our day, with our lives. About what I want for her, and what I want for myself. Laying eyes on this baby and thinking about what I did to get her here casts everything around me in a powerful new light. If I can birth, I can dream—and more than dream, I can do: I can navigate around obstacles. I can make plans. I can take the lead. I can oversee. With Georgia, I’ve had my first taste of real power—life-creating, life-sustaining power—and I want more.

It’s time, I think, to dream forward.

* * *

—

Dreaming forward, as it turned out, landed me in the world of public relations, an arena that worked well with my love of stories, and with the relationships I’d created with writers and editors while working with Cheeba Sound and Joe’s Pub. I named my company Jodie Becker Media, and it was my first opportunity to put ownership firmly in my hands.

My plan was to keep my business small, intimate, and based at home, because the flip side—scaling and expanding—would mean getting office space and leaving Georgia at home to go to work each day. I wanted just enough clients, three to five, to keep me engaged but not overwhelmed. The goal was to have one fluid life like many of the people Serge and I encountered every day—a full life that smoothly flowed between family and work.

My manifesto became “I choose clients that I naturally gravitate toward.” I went into business with big corporations and young fashion designers, eccentric musicians, brilliant writers, film festivals, fashion events, and avant-garde magazines, all—somehow—while keeping Georgia close by my side.

I learned to multitask during these years, working at my desk for eight, nine, sometimes twelve hours a day—sometimes juggling nursing, cooking, and holding a meeting simultaneously. I’d throw a little blanket over Georgia’s head to offer a bit of privacy but otherwise keep it moving.

Georgia was content, as long as she was nursing or snuggled in my arms.

Just a handful of hours of sleep each night became the norm. By the end of the workday I was spent, I had used up all my nice emotions keeping Georgia occupied and happy, and my ability to think rationally and calmly was depleted by my clients. At night, if any little thing went askew, like, say, Serge coming home an hour after he promised, I would flip. I’d scream and throw things across the room, a book or a framed picture—anything that was in arm’s reach.

Serge standing there quietly in the midst of my tantrums made my chest feel as if it were about to burst open. So calm in the midst of my storms, so nonchalant about everything, coming and going as he pleased—it all made me furious. And his intended compliments—“But it’s so sweet seeing you and Georgie always together,” or “The apartment looks great, babe!”—felt like daggers flying straight at me. His sweetness landed on me like a threat.

While Serge could put on and take off one hat at a time—wearing “father” sometimes, then “boss” or “lost-in-the-clouds-creative” at other times—I was learning that that kind of versatility wasn’t open to me.

One night, I came face-to-face with my rage. “You said you’d be home five hours ago! I’ve been holding Georgia in my arms all day, Serge!” The clang of the metal as the scissors hit the bookshelf and fell to the floor startled us both. I stood still while Serge looked at me to see what I’d do next. His eyes shifted slightly down to Georgia and softened. Without saying a word, he walked slowly, coldly, over to me, taking the baby out of my tensed arms. Then he turned and left the apartment, leaving me to sit in my shame.

You would think we’d change our routine after that incident, that my anger would have told us to do things differently. But going forward, Serge’s schedule didn’t budge, and mine didn’t, either. Meanwhile, the anger kept piling up.

I’d snidely joke with Serge that I needed a wife, someone to assist me and keep all my balls in the air. He’d look confused and walk away, his min

d on something else.

As much as I loved my work and my family, I was starting to understand that “wife” was often synonymous with “administrative assistant”—someone who pulled it all together but never, ever called the shots.

* * *

—

The tension between Serge and me grew. We argued over his freedom to come and go as he pleased versus my always-on-call reality. It was partially my doing; I felt Georgia needed my touch and my protection. She came from me, grew out of me, had shared my blood for months. Even after she left my body, I couldn’t fully separate. Even the mere idea of a nanny or even Serge taking her where I couldn’t see her, smell her, touch her, sent me into a panic. Serge, on the other hand, could easily disconnect from us and go about his day at the office, not worrying or checking in until the evening.

I was seeing that my life as a woman was very different from Serge’s as a man. That the obligations, the expectations—both spoken and unspoken, even our internal compasses—were fundamentally different. And at times, I felt trapped. This “womanhood,” I was learning, came with an extra layer of responsibility.

All my life, my environment had been created by the people around me. I’d asked everyone important—Mama, Daddy, Ramona, Grandma Gloria, Serge—to have purpose in and over my life. Up until this point, the point of motherhood, they had led my way.

But with Georgia, I would do things differently.

I loved her fiercely, and I felt for her with the passion of a possessive lover. I knew that if Serge and I didn’t allow her the space to be big and free, as girls so often don’t get to be, people would try to tell her who she was and what she needed to do. They might try to explain her power with caveats, as it had so often been done with me. Be smart but not grad-school-smart. Be opinionated but not inappropriate. Be self-sufficient but not an old maid. So I vowed to give Georgia what I had only sometimes—room to wander, to experiment, and to learn to be imposing. For her, I would create an environment for her freedom to grow.

The Bold World

The Bold World